Review by Rosa Reitsamer of the exhibition I am not a Feminist. I am normal., curated by Marlene Haring and Anthony Auerbach, Austrian Cultural Forum, London, 2004, published in Art in Sight, London, January 2005

Who wants to be a Feminist?

More than thirty years after female artists such as Valie Export, Sanja Ivekovic, Carolee Schneemann and others developed their practises along feminist theories, ideas and concepts, a recent group show at the Austrian Cultural Forum, London, was entitled ‘I am not a feminist. I am normal.’ The exhibition was conceived by the artists Marlene Haring and Anthony Auerbach as a parallel project to the Valie Export retrospective at the Camden Arts Centre and brought together a small selection of works by younger artists. Not least because of direct reference to Valie Export, the title of the exhibition, as well as the works which are collected under it, pose several questions which refer to an obviously ambivalent relationship that young female artists have with feminism.

Now more than ever, many young female artists do not like to describe their artistic practise as explicitly feminist, for the combination of art and feminism has brought many female artists more stigmatisation than fame on the traditional art market. ‘Feminist art’ is often used to set boundaries anew and to perpetuate established clichés. Feminism is not an aesthetic and does not inevitably produce ‘feminist art’, rather, feminism is a tool for political analysis of women's experiences in a sexist, racist and anti-semitic culture. However the main problem seems to be that both the art establishment and the feminist community understand feminism as a specific aesthetic or characteristic style. A feminist standpoint gives rise to specific questions about art production, but the questions, aesthetics, and styles of female artists are multi-faceted and heterogeneous. They cannot be declared as one standpoint, one aesthetic, or one style. Yet the title ‘I am not a feminist. I am normal.’ seems to suggest one feminism or one feminist standpoint which is perceived to be different or even abnormal.

In the 1970s, female artists questioned the representation of the female body in order to highlight the depiction of women as passive objects of male desire. The encoding of the female body in society, its stigmatisation and devaluation, has since been at the centre of many women’s art production. In their artistic practise the ‘subject woman’ is no longer passive, but refers to an oppressed existence, which, in art production, brings out a specific politics of identity. This once revolutionary idea provokes young female artists to disassociate and distance themselves from feminism. At the same time, identity politics, has since the 1990s, become an instrument of the mainstream of the traditional art market. The expectation of the art establishment towards marginalised and discriminated female artists is manifested in the demand to make their identity a central theme, but without referring to the history of oppression and resistance. Therefore an identity politics is demanded and expected, but one that is freed from its political content and demands, and thus floats in an empty space.

Against this background, how can the title ‘I am not a feminist. I am normal.’ be understood? Is it supposed to be an implicit critique of the traditional art market? Or a critique of the feminist community, which searches for a feminist and/or female aesthetic in art production by women? Or does the title want to dissociate the exhibition from the artistic practise of women who understand themselves as feminists? But the essential question is: Why would it be necessary to distance oneself from a tool of analysis of power relations? Do racism and sexism belong to the past because women and people of colour are allowed at universities? Is the discrimination against women and people of colour passé because identity politics have become mainstream in the arts, or because the questioning of discrimination is associated with a specific generation of women, generally regarded as old fashioned, lesbian, and separatist? Each generation of women wants to do things their own way, and obviously has to define itself in contrast to the generation of their mothers. But can a title like ‘I am not a feminist. I am normal.’ express this attempt at self-definition without supporting a neo-liberal social order? Probably not, because this self-definition seems to function through fixing and establishing normality and abnormality, through constituting a ‘self’ and an ‘other’, through determining oneself as a member of normality. ‘I am not a feminist. I am normal.’ seems to postulate normality. Except that what is supposed to be ‘normal’ remains uncertain, at least until visiting the exhibition. In contrast, the ‘abnormal’ is clearly defined: feminism.

On visiting the exhibition the same questions arise again and again: how is normality expressed in artistic works? How have the questions changed for young artists since the 1970s? How are identity politics and sexual politics thematised in the practises of young artists? I will try to answer these questions by walking through the exhibition.

Katherine Araniello: I Like That, video

Katherine Araniello: I Like That, videoEven before visitors enter the gallery at the ACF, they are welcomed by Katherine Araniello’s glamour-orientated pop video I Like That and Marlene Haring’s two-part poster piece Nivea (1999) and Nivea (2000). Araniello questions the notions of normality in the sexualised pop industry. How can one consider being ‘normal’ for a disabled woman who wants to have fun? How can identity, sexuality and pleasure be visualised for a disabled woman without falling back on pop icons like Madonna or Britney Spears? The absurdity of a division between ‘normal’ versus ‘abnormal’ is at the centre of her work and oscillates between humour and the attempt to thematise a previously seldom told story. I Like That not only contradicts the title of the exhibition, but also the ostensible normality of the Austrian Cultural Forum (ACF). Founded in 1955, ACF is located in a residential area of Knightsbridge and recognisable from the outside only by the Austrian flag. Inside, the furnishings, especially the red carpet, lend a certain old-fashioned character to the building. Here normality is expressed through references evoked by a specific interior decoration and by the ACF programme structure with an emphasis on looking back at Austrian classical music, ‘Vienna 1900’ and Austrian film of the post-war period. The works by Araniello and Haring presented in the entrance hall are a disruption of this artificially-constructed normality.

Marlene Haring: Sex, Death, Nivea, installation, exterior view

Marlene Haring: Sex, Death, Nivea, installation, exterior viewIn her piece, Haring plays with the pose of the white pin-up girls. She questions the borderline between woman and animal as well as the idealised beauty of women. In Hollywood cinema from the 1930s to the 1960s, white, blonde women played a prominent role and were a compliant projection surface for sexual desire. Haring picks up on these fantasies by satirising women’s alleged proximity to nature and the animalism in their existence by humorously confronting the two posters, namely a naked blonde and a woman covered in hair. Testing the limits of a female subject-position in the arts was also a frequent provocation in Haring’s work in the collaboration Halt+Boring (1991–2003, together with Catrin Bolt). Their pieces like Corrections and Call Boys (a video installation which displayed film of the artists having sex with male prostitutes they hired with the money they received for their contribution to an exhibition in Salzburg, Austria) repeatedly take up the male-connoted genius-gesture and give it short shrift with a wink of an eye and without a warning finger.

Carey Young: Optimum Performance, video

Carey Young: Optimum Performance, videoIn the gallery itself there are, among other pieces, numerous video monitors, which are not presented in a conventional exhibition design, but attached to the wall or placed on boxes. Optimum Performance by Carey Young is a video documentation of a performance piece created by the artist for the Whitechapel Gallery in London. The documentation features an actor who delivers a rousing motivational speech to the gallery audience as if they were a group of his own professional colleagues. While Haring’s and Araniello’s pieces suggest a direct link to the title of the exhibition, with Young’s piece it is much harder to find this connection. Optimum Performance can be read simultaneously as a functional tool designed to manipulate the abilities of the audience and as a subtle critique of the institutions and systems of the art world.

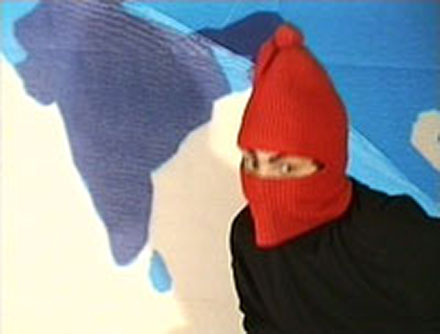

Mikki Muhr: On Air, video

Mikki Muhr: On Air, videoIn Mikki Muhr’s video, On Air, a woman in a balaclava helmet appears repeatedly on the screen and sings ‘Hu-hu, nobody knows me’, while the camera woman gives instructions and comments. On Air is a humorous exploration of Muhr’s own identity as a female artist. The continuous exit and reappearance of the masked woman, who exposes only her eyes to the public, poses the question of the location of a strategic and political place for female artists. However the position of the monitor high up in a corner took away some of its directness, through which its humorous and absurd elements would be able to fully unfold.

The next stop in the gallery space is a stage which was used on the evening of the opening and otherwise can be used as a place to rest. The performance Burn the Bra by Ursula Martinez impressed by its pointedly short staging of a naked woman in a fur coat. Martinez stepped onto the stage, threw the coat away, asked someone to light her cigarette, then used it to spectacularly set fire to the little white triangles attached to her nipples and pubic hair, butted the cigarette out in her vagina and left the room as quickly as she had entered it. She left behind an enthused audience, who took nearly as long to comprehend the performance as it had actually lasted.

Marlene Haring: Sex, Death, Nivea, installation, interior view

Marlene Haring: Sex, Death, Nivea, installation, interior viewThe view one might have got out of the window of the gallery onto the street is blocked by the installation Sex Death Nivea by Haring. The installation consists of two trestles with a table top at the height of the windowsill. On this there is a framework covered with a white tarpaulin. The light-flooded shop window-like space behind it can be seen neither from the inside because of the white material covering the view, nor from the street, as the window was covered with a thick layer of Nivea cream. The installation refers, in part, to the body, its constructedness and perishability, for with the passing of time, the thick, opaque layer of Nivea decays and permits an uneven view of the interior.

Elke Krystufek: Same Time, Next Year; Elke Krystufek and Sands Murray-Wassink: The Naked Conference, videos

Elke Krystufek: Same Time, Next Year; Elke Krystufek and Sands Murray-Wassink: The Naked Conference, videosIn front of the installation on the right there are two boxes, with a monitor placed on each of them. One shows Elke Krystufek’s Same Time, Next Year, the other one The Naked Conference by Krystufek and Sands Murray-Wassink. In the video Same Time, Next Year (1997–2003) Krystufek plays both parts of the two-person drama by Bernard Slade, which was a big success on Broadway in the 1970s. The comedy describes the effects on the couple of an affair lasting for twenty-six years consisting of once-a-year meetings in a hotel. Their identities are stamped by economic crises and socio-cultural events which reflect global, national and private power relations. The Naked Conference documents a naked public discussion with audience participation about their photo project Elke & Sands: Equalities, Equivalences under feminist viewpoints. The documentation takes up several thematic fields of feminist theory such as comparisons of female heterosexual and male homosexual body, female and male gaze, sexual practices, voyeurism and pornography, and relates them to art practices as well as art and media theory. The Naked Conference is a journey through history, theory and practice with numerous feminist-political intermediary stages. It shows that even in a globalised post-feminist age there is no escape from the persistent questions of one’s own identity.

Anna Jermolaewa: Three Minutes of Trying to Survive, video

Anna Jermolaewa: Three Minutes of Trying to Survive, videoAnna Jermolaewa’s video piece, Three Minutes of Trying to Survive, shows a group of rocking dolls which slowly begin to sway. However, they quickly become individuals, little monsters attacking each other, pushing each other out of the picture with loud crashes. The force which moves the dolls remains invisible. Three Minutes of Trying to Survive questions mechanisms of power that create hierarchies and the brutality allegedly necessary in order to survive. The little monitor mounted on the wall pointedly underlines how the powers which structure society are not necessarily monumental or even visible.

Sands Murray-Wassink: After VALIE EXPORT ...

Sands Murray-Wassink: After VALIE EXPORT ...The two remaining pieces in the exhibition are located on two opposite walls. Murray-Wassink’s collection consists of a pair of torn jeans with the title After VALIE EXPORT (Gay White Western Male Bottom) Aktionshose: Genitalpanik, the two photos Sands Eating Himself and Feminist Gay Queer Sands 1974/lemon pie/Genitalpanik **(V.E.)** and the drawing Portrait of (down and out) lemon pie/freaky friday/dinky hocker shoots smack! (sands stv).

Julia Wayne: Untitled record

collection, LPs

Julia Wayne: Untitled record

collection, LPsJulia Wayne’s Untitled record collection consists of LP covers of female rock and pop musicians. Wayne’s works deal mostly with the distribution, encoding and consumption of messages and images in public space. She questions the supposed boundaries between the public and private, the spaces of consumption and of critique. However, the present piece explains itself only in parts. It remains open whether these twenty-one LP covers with diverse images of female rock and pop stars refer to the heterogeneous representation of female musicians in the pop industry, and if they are at all able to question it. Wayne’s other contribution addressed the theme suggested by the exhibition title directly in a work entitled I repeat. I do not affirm, which consisted of a series of statements on the pattern ‘I am not ... I am ...’ When we read, ‘I am white. I am normal. ... I am a woman. Am I not a man? ... I am a woman. I am identified.’ among various correlations and contradictions, we are forced to examine the ‘I’. These apparently affirmative statements contradict one another and the piece reminds us that the meaning of a statement cannot easily be separated from who says it and that the ‘innocent I’ can mask a multitude of identities and subjectivities.

Sands Murray-Wassink’s work on sexuality and identity is however much more direct. He pays homage to the work of pioneering feminist artists such as Carolee Schneemann and Valie Export and adopts some of their strategies for attacking or overcoming male heterosexual and homosexual inhibitions, prejudices and norms. Murray-Wassink, who describes himself as Western homosexual male artist, occupies a special position in this exhibition in two respects: he is the only man in the exhibition, and it is he who refers directly in his works to the practise of female artists of the 1970s.

Walking through the exhibition shows that normality has as many variations as there are feminist standpoints. The questions for young female artists have only gradually changed since the 1970s, yet earlier provocations and revolutionary strategies have undergone countless redefinitions and revisions. It seems interesting that the curators chose a piece by a homosexual male artist to refer to the history of pioneering feminist artists. The question remains: Who wants to be a feminist, when the connection of feminism and art for certain young women (artists) seems to be a problematic one, if not a dubious one? Who wants to be a feminist, when feminism is allegedly located outside normality, and today it seems more important then ever to be a member of normality? The hope remains that women, who organise ladyfests, publish feminist magazines like n.paradoxa, or run archives like Cinenova are not afraid to be feminists and to call themselves feminist.

Rosa Reitsamer